Nangran

My mother's mother's name was Elsie but everyone called her Nan. To my brother and me she was Nangran.

When I think of Nangran, I am overwhelmed with little pieces of memories, some complete episodes, and some fragments that float about just out of reach.

My earliest ever memory is of her. We were living in Paris and I was three years old. I have a clear image of her stepping down from a coach into the waiting crowd. I am high up, on Dad's shoulders probably, and she sees me and waves.

Back in England we saw her more often, going after school or at weekends to where she lived with Grandad in Gravesend, Kent. Only later did I ever think of Gravesend as a depressing name for a place.

When the new tiny five pence pieces came out in Britain, she said her arthritus made it impossible for her to pick them up, so she saved them in a jar for our visits, and we'd carefully carry our little stash down to the petrol station with Grandad, where we would buy pic'n'mix sweets and chocolate that we would munch happily all afternoon.

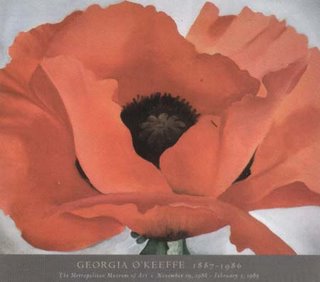

She loved poppies and hated elephants.

When she looked after us after school, if Mum and Dad were both working, she'd give me milk with a spoonful of sugar stirred in. It was clear I was not to tell Mum; our little secret.

Her arthritus deformed her hands into knobbled pincers but her nails were always polished pink and the skin on her hands was the softest I've ever felt.

When we stayed the night, we would always watch Coronation Street and play cards. If I hear the theme music to Coronation Street when I'm in England, I'm immediately taken back to her green corner sofa, the polished table on which we played cards, and the busicuit tin that was never out of reach.

She was tiny ('I'm four foot eleven and a three quarters!') and when she had driven ambulances during the war, she had needed a mountain of cushions under and behind her, so that she could reach the pedals.

She always took my side in the 'Mum, I want my ears pierced' arguments. Mum said little girls shouldn't mutilate their bodies, 'but it's pretty' Nangran would say, 'I'll take her to have it done'. Mum held out for a long time.

When we went to her beloved golf club she would show us off to her friends in the eternal grandchild competition. 'Isn't she tall' her friends would coo, 'is she going to be a model?' and I would blush with a mixture of pride and embarassment. 'Everyone thinks my granddaughter is going to be a model', I remember one old lady spitting out one afternoon.

She always praised my Dad, and regularly confided 'I do like a man with a beard'.

Nine days before my twenty-first birthday, Nangran died. Granddad had gone before her, and she had been valiantly struggling along on her own ever since. Physically crippled by arthritus and pained by her old body, Nangran was bright and mentally alert until the end.

In nine days I will turn twenty six. I still imagine Nangran's reaction to things that are happening in my life. I can still hear her voice, her 'ooo-er' exclamation of surprise or admiration and her golden chuckles. She was an incredible woman. I still miss her.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home